This post is 1st of 3 in the series aimed at discussing ways Silicon Valley and European tech scenes could contribute to and gain more from each other. The series are an expansion of a short speech I gave at Slush conference in November 2013 (video of which should be online soon) but I believe this topic is calls for more discussion and thinking along than 15 one-directional minutes on conference stage._

If you were to sit in the audience of any European tech summit these days you get soaked in action around you. Would it be TechCrunch Disrupt Europe, LeWeb, or the raising 5000-attendee rocket of the region, Slush in the November darkness of Helsinki – there is no arguing that the European startup scene is in its most bustling, vibrant shape ever.

Yet, a lot of this exciting renaissance seems still to be constrained to the Old World continent.

I’m proud to be Estonian and European, but recently realised that very soon I have been living in California for 10% of my life. I got a first hand experience of the first internet boom as an exchange student at the super-wired Monta Vista High School in Cupertino in 1994 and have later returned with frequent travel for Skype and extended stays to pursue a degree at Stanford and now as an EIR with Andreessen Horowitz.

As a graduate student last year, amidst Stanford’s infamously mixed community of leading academics and tech industry practitioners of this planet I was shocked that Europe hadn’t just become “less relevant” as I expected, but it had virtually ceased to exist.

During four quarters of the year, I heard one professor make one joke about short term macroeconomic troubles of Greece. And then there was a charming, well-suited British banker visiting our Private Equity class. That’s it. No European startups, no cases of European success stories or failures.

I’m far from blaming the school for a hostile omission of something obvious. Because Europe is just not obvious any more.

Talking to many people about this gap I gradually found that there a quite consistent mental hierarchy of “important places” that has developed for an average person who is building or investing in companies or studying on the West coast of US, especially in Silicon Valley:

1. Silicon Valley itself. Opportunity cost of going out of the bustling 30 mile radius of Sand Hill Road is just too high to pragmatically even take some time to investigate it for many.

2. US East coast – yes, tech scene is happening in Boston and New York, but it is more like “try to fly over once in a month or two”-happening, not “MUST be there NOW”-kind of urgent-happening. And you hear untriggered mentions of any startup locations in between, like Denver or Austin even less often.

3. China – massive tech companies do rise in China, go public in US, seek to invest in the Valley. People move back & forth between Pacific coasts – and it makes sense when you look at the globe. Valley starts to look more and more towards China for innovation trend predictors and expansion opportunities, not the cheaper production of 2000-s.

4. Rest of Asia – India’s diaspora links with US are strong, South-East Asia’s growth is hard to miss and there is interesting mobile movement always happening in Japan, but… it still only translates to minor tangible business across Pacific, compared to all the action locally.

5. “I took my wife/husband to Paris last year for our anniversary, and we dropped by Rome – it was so romantic! Europe is wonderful!” Enough said.

This reminded me of a much-discussed essay I’ll Gladly Pay You Tuesday (coincidentally published by Stanford’s Hoover Institution) by Toomas Hendrik Ilves, a former Ambassador to US and now the President of Estonia. Ilves pointed out the shift of US foreign policy attention from transatlantic to transpacific: “We here in Europe and even our friends, the transatlanticists in Washington, now realize that the U.S. presence, its interest in us, was not a done deal forever,” and analysed the long term impact of this change for ally continents. While the terminology is different, to me it seems the gap is growing likewise between the private tech venture scenes. Have we found the one phenomenon where Silicon Valley is in complete sync with Washington?

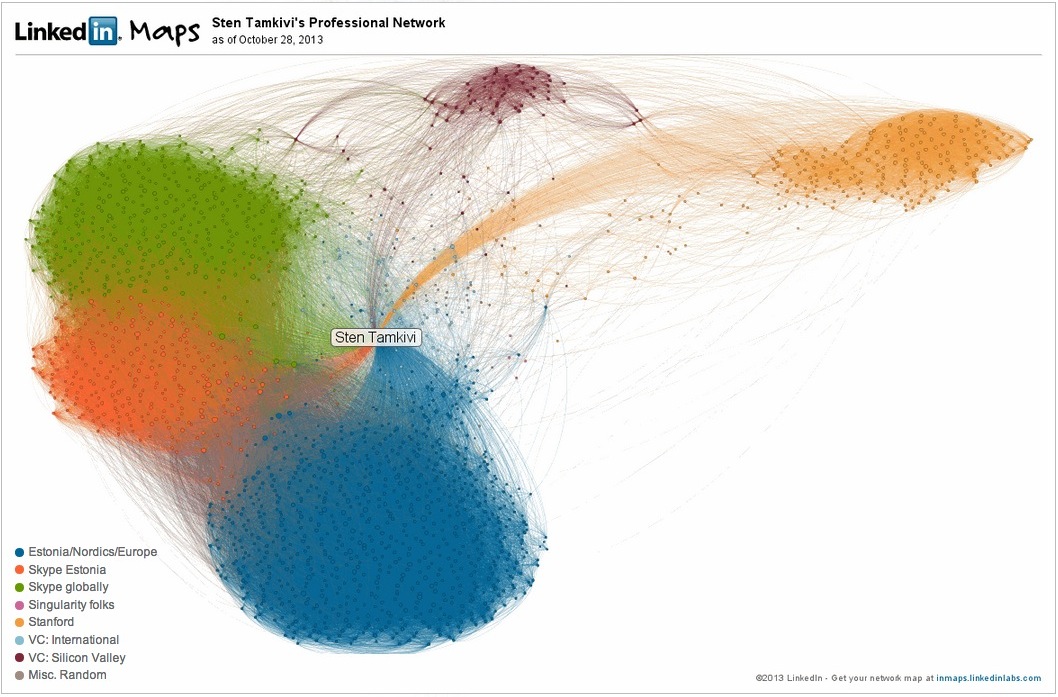

To validate this broad sentiment on personal level, I turned to LinkedIn Labs’ InMaps. I’ve been a disciplined user of the networking tool and my listed contacts are a set of people I have actually worked together with, or at least met with in person. Mapping my network out visually with our particular topic as context confirms how Estonia, Nordics and Europe in general are a tightly knit blue blob. Skype, where I spent 8 years in Estonia (orange) and internationally (green) is an entire organism in itself.

And then, Silicon Valley venture capital and serial entrepreneurship circles float as a distant burgundy cloud. And the international graduate students and teachers body of Stanford is even further out on the right:

Those familiar with Granovetter’s theory about the strength of weak ties should feel a wave of joy here – the ties linking US and EU scenes are indeed still weak, routed through a relatively small number of connecting nodes in between the clusters. We know there are benefits of weak ties, but then again, there are virtues to tight knit communities talking to each other frequently.

Given the current state of ignorance I see a massive opportunity for (re)building some fresh bridges between US and Europe. In general, the aim should be sharing the successes and learning from each others’ mistakes and in the next few posts I will try to go a little deeper on why and how I think Europe and the Valley should care about each other.

Continue reading: On Bridges, Part 2: Why Should Europe Care for Silicon Valley >>